Colour Is Enough – The Art of Tanya Goel

For some artists, the path unfolds slowly, shaped by detours and reinvention. For Tanya Goel, it was always quietly present—a steady instinct that endured through doubt, discipline, and distance.

From childhood hours spent drawing and making, to years at the Yale School of Art, and now at her studio in Delhi, her practice has remained centred on one thing: looking. Not fleeting glances, but sustained observation, a deliberate encounter with colour that asks the viewer to pause and remain present.

In this conversation, Goel reflects on education and self-doubt, on the value of prolonged attention, and on why her work resists explanation. What emerges is a practice defined not by spectacle or statement, but by patience, visual memory, and a commitment to seeing—again and again.

Describe your path to what you’re doing now.

It has been a fairly straightforward path—though not without obstacles, and certainly not without self-doubt. I’ve always known I wanted to be an artist, even when my understanding of what that meant was limited to romanticised notions of artistic aura and madness.

As a child, my mother would read artists’ biographies to me, and drawing, pottery, and craft-making—filling colour into shapes—were always my favourite activities. I recognise the privilege in being able to continue doing much the same work till now. I strongly believe that art-making is both an extremely selfish and deeply self-indulgent act.

After completing my master’s degree at the Yale School of Art, I lived in Brooklyn for a period before returning to Delhi to establish my current studio.

What was the most valuable lesson you learned during college?

During my undergraduate years, I learned the value of observation—how to observe at length and with sustained focus. This helped strengthen my visual memory and taught me to distinguish between seeing and looking.

Seeing, whether our eyes are open or closed, is a continuous and subconscious mechanism, much like breathing. Looking, on the other hand, is a conscious pause within the act of seeing. Blinking is an involuntary movement that interrupts or recalibrates that act of looking.

How important do you think it is for an artist today to have a formal degree?

I go back and forth on this question. There have been moments when I wished I hadn’t spent seven years in formal art education. I don’t think it is necessary—there are many remarkable artists, living and dead, who never had a formal art education.

That said, for me, it was a valuable experience that has supported my practice and professional trajectory. More broadly, what matters is being part of an environment where one can interact with like-minded individuals, engage in critique, and pursue shared interests. Educational institutions can offer a protective bubble for intellectual growth, but they can also feel removed from the realities—and the “monsters”—encountered outside institutional spaces.

Have you had any mentors along the way?

I consider many of the professors and peers I’ve worked with to be mentors. It was a privilege to receive guidance from Vasudevan Akkitham in Baroda, Rochelle Feinstein, Peter Halley, and Robert Storr at Yale, and Peter Nagy in Delhi.

Beyond individuals, I’ve also found mentorship in voices that emerge from works of art, literature, and film—sources that have sustained an ongoing internal dialogue and helped shape my practice through self-critique.

Which artists do you look to for inspiration?

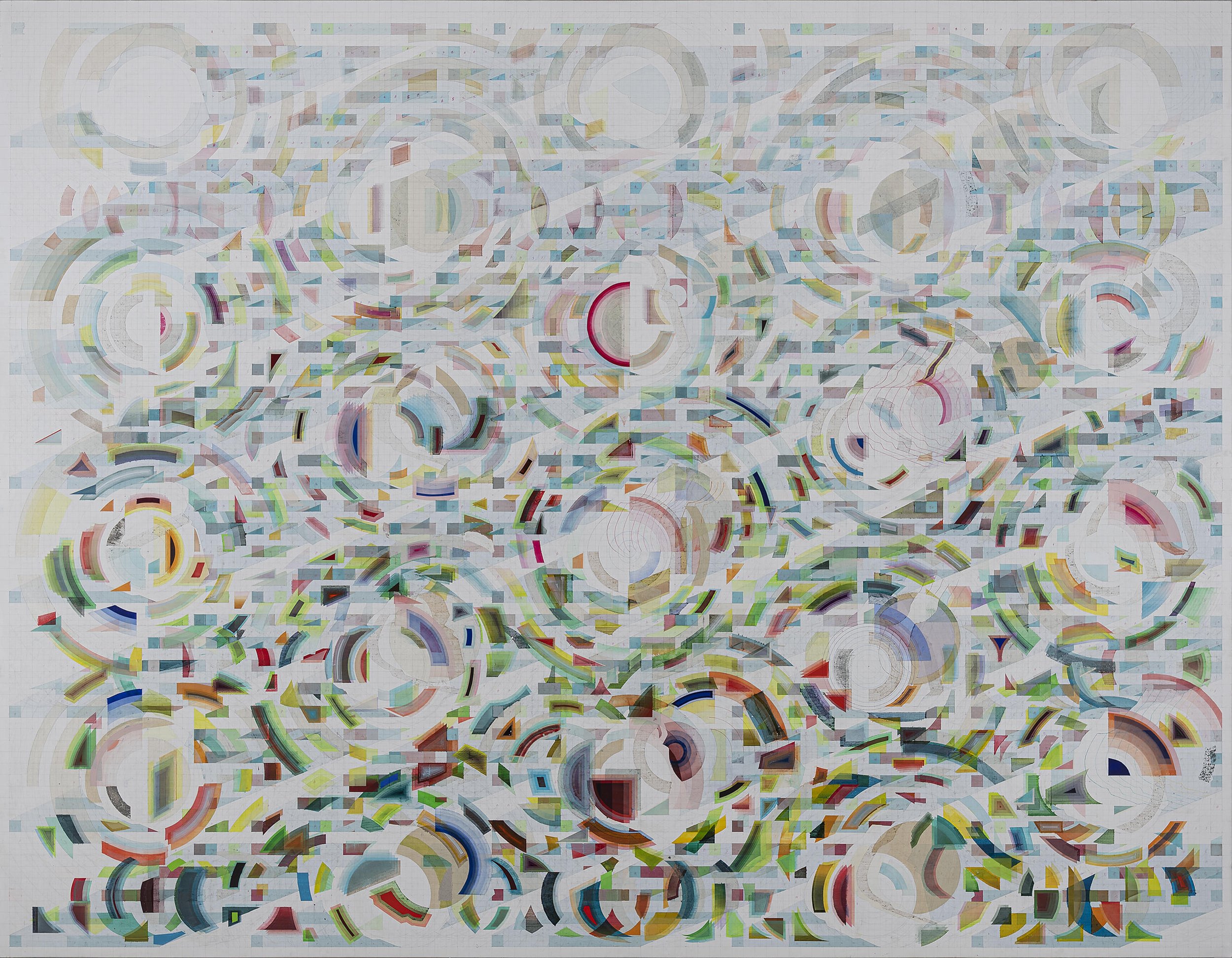

My points of reference have shifted over different phases of my life, so it’s difficult to name a fixed group. That said, I’ve maintained a long-standing affinity for the work of Joseph and Anni Albers, the Russian Constructivists, various forms and periods of miniature painting, and the histories of textile weaving.

How did your work first start getting noticed?

I had my first exhibition in Bombay a year after graduating from the Yale School of Art. It was titled “2 Inches Left From Here.”

Who was your first patron?

Jay Mehta.

Are you part of a creative community, and is that important to you?

I see myself as part of a global creative community, within which there are peers I engage with more closely. My studio also functions as a community of sorts. I have a research and development department where assistants and interns are continually experimenting with and discussing colour.

Is there a particular message you try to communicate through your art?

The idea of art as a carrier of messages does not particularly interest me. What I seek instead is a visual connection—an experience rooted in the act of looking at colour.

What is one lesson you would want your future self to remember?

To collaborate more, even though it goes against my natural inclination.

Which contemporaries’ work do you admire?

Hemant Sreekumar, Ritika Merchant, and Amy Beecher.

Photo credits: Sukant Deepak,Nature Morte